There is an erroneous notion prevalent in todays soceity that heritage – is something colonial, something ancient. The latest to fall prey to this is the Kala Academy – a bustling centre for the arts on the banks of the River Mandovi in Panjim. Recent leakages have brought the tarpaulin over the affected parts and along with it, calls for the structure to be demolished. A certain part of it, that is. But demolishing part of it and demolishing it entirely is very much the same thing, and must be prevented at all costs.

The Kala Academy was set up by the Government of Goa in 1970 to ‘promote the cultural unity of the territory in the fields of music, drama, dance, literature, fine arts, etc’. It was designed by the legendary Architect Charles Correa, a Goan himself, and was completed by 1983. It instantly became the cultural hotspot in the city, and is a special building in Correa’s international repertoire, being his first in Goa, and is one of the finest examples of modern architecture in the country. For the people of Goa, it has an even greater underlying significance – an additional layer of meaning. In order to understand this, though, one would need to know the context amidst which the building entered the scene.

Source : Charles Correa Foundation

Goan architecture reached its peak in the 19th century – when a rise in social rank coupled with improved economic conditions, among other factors, forged a strong Goan identity. This was directly mirrored through the ostentatious homes and popular public buildings that sprung up in this era. The construction boom in the mid 1900s however, put an unprecedented pressure on the Goan landscape.

The pace of life has always been slower in Goa – but all of a sudden, new factories, an airport, high-rise aprartment blocks and the like all entered the foray with no local architects to guide the process. Designs were bought in from Bombay, or Portugal. New materials like concrete and glass entered the scene, but were not always used appropriately. There was an apparent lack of sensitively designed modern buildings. This lack of character was the case during the Liberation and persisted subsequently thereafter.

What Goa severely lacked was a modern icon – something to serve as a stronghold to pave the way forward. And that is exactly what Charles Correa delivered with this building. Here was finally a building of pedigree, a building that immediately and raptly resonated with the public – as it reflected the aspirations of a modern independent society, but at the same time was firmly rooted in its past.

Source : Charles Correa Foundation

Almeida, Sarto and Jaimini Mehta reinforce the importance of the building in this carefully written excerpt which deserves to be mentioned in full :

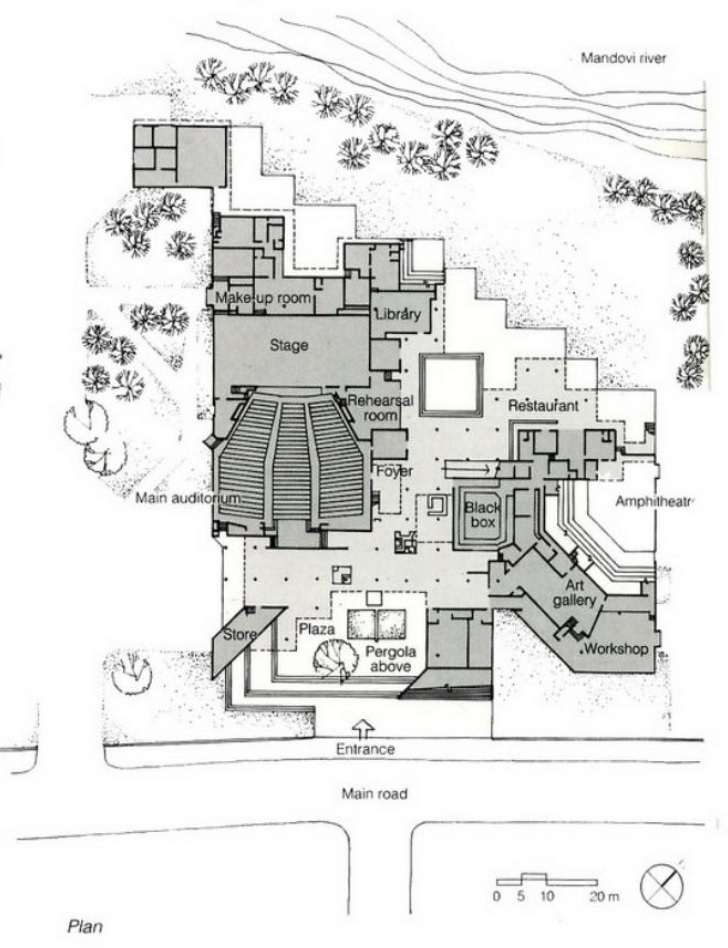

The Kala project undertook significant innovations in spatial organization. A modernist plan-form of post and beam construction on an orthogonal grid offered the architect the necessary variation in dimensions demanded by a programme that makes use of several performance halls, exhibition galleries, informal public gathering places, etc.

The relatively low rise mass is spread horizontally and organized around an innovative ground plan with an open ‘street’ going through the entire building. This allows one to enter the building without being self-conscious about entering; it makes an otherwise serious public institution seem less “institutional” and more relaxed and appropriate. It offered respite; a new way forward for society.

Both these projects are significant as they created an identity of contemporary Goa and did not merely express a commonly held idea of what Goa is all about. In a contemporary context, they reinterpreted elements — the clustered village and the public street that have only an indirect association with Goa, derived mainly from the Portuguese past. However, they speak of a large and remembered part of Goa and to that extent are credible and successful attempts at defining and expressing our identity.’

On display in the Academy are Correa-esque elements – the transition between enclosed and open to sky spaces, the non-building, the use of visual imagery – like Mario’s figures in the Dinanath Mangeshkar Auditoium or the trompe-l’œil in the open street. These blur the distinction between real and illusionary, and provide a theatrical setting to a theatrical place. Goans will subconsciously relate to this imagery that adorns the transitory spaces – similar to the elaborate backgrounds used in tiatrs (Goan dramas – which are a regular event at the Academy itself). For architecture students, it is a marvel, a name that is at the tip of their tongues. For locals, it is arguably the most famous modern cultural building – one that no one needs introduction to.

Source : Charles Correa – Kenneth Frampton (Thames & Hudson 1997)

Perhaps what makes the Kala Academy so distinct is how it ‘gives back to the city’. In the 21st century, public space has become all the more an important commodity; a direct physical component of human rights. The very essence of the whole design is the internal street which, through little subtleties (broad steps, use of levels, light pergolas), draw the pedestrian inside from the main road and towards the Mandovi river, with chai and samosas on the way at the cafeteria. By crafting this experience, Correa has given the plot of land back to the public – a rare proposition in this day and age, and truly ahead of its time considering it was built around 35 years ago.

This breezy corridor is incredible. On a regular evening, one can find people from all walks of life and of all age groups spending time out on these broad steps chatting away. It is arguably the most inviting building in the country.

The other amazing facet of the building is its low mass and human scale. It lacks ‘sculptural and monumental ambition’, as Himanshu Burte puts it, in a good sense. As Correa implemented in several other projects, the non-building takes the back seat. By being subordinate, it facilitates activity and encourages wandering. Its greatness therefore, lies in its nothingness.

Over the years, the Academy has contributed immensely to the cultural identity of the region. Within its auditoriums, amphitheatres and classrooms, young budding musicians, tiatrists, artists and other talents have been groomed and have gone on to excel.

For all these reasons, the Kala Academy is nothing short of heritage, and is one of the most, if not the most important modern building in the whole of Goa. It was an instant favourite of the people in the 80s, has endeared itself to each successive generation almost seamlessly, and continues to be a big hit among the present generation. It goes to prove that heritage has no age bar, no qualifying ‘number of years’. It definitely warrants preservation at any cost.

Source : Charles Correa Foundation

What next for the building? After the government made claims to demolish the structure, the High Court has stepped in and taken suo motto cognisance on the matter. It ordered the state Government to sign an affidavit stating that they would conduct a credible structural audit of the building and would avoid making any hasty decisions regarding its demolition. Various fraternities has come out in solidarity, all appalled at the decision to demolish the building for issues as trivial as leakages.

Nondita Correa Mehrotra, daughter of Charles Correa, an architect herself, and also the Director of the Charles Correa Foundation expressed:

‘The CCF is confident that we have the knowledge pool to work with the government in finding a solution for structural restoration of the building. The foundation would like to appeal to the Government of Goa and the citizens of Panaji to involve us in the process of addressing the problems that have arisen at the Kala Academy, in a way that preserves the architecture, art and integrity of the building’

She has also started an online petition which hopes to raise as many signatures as it can before the Court Hearing. At the time of writing, it has already amassed 18,000 signatures.

Since its inception, several attempts have been made to reinterpret Goan architecture in today’s context. And though they may be good and honest, Kala Academy will always be the first serious attempt to do it, and probably the most endearing one of them all. Hopefully, the building will be conserved in a sensitive manner. The locks have come on the affected parts of the building while the matter is being resolved. But the open street is, and always will be left open. Everyday, hundreds of people continue to take part in this orchestrated walk, unknowingly experiencing the magic of Charles Correa.

I am truly heartbroken to know the govts plan. I was among the pilot batch of kala academy in Kathak. The academy has been my home literally with endless hours of practicing and performances in dinanath auditorium, black box, amphi , open space and open air audi. I sincerely hope the govt of Goa finds a better solution with CCF. I pray fellow Goans and artistes stand together for Kala Academy.